.gif) |

The word "conjugate" means "to join

together," and combining multiple methods within a

single workout can lead to a stronger, faster, more

well-balanced body.

By Greg Werner,

M.S., CSCS, SCCC, ACSM-HFI, CSNC

For

athletes, performance and the prevention of injury--not

aesthetics--should be the motivation for strength

training, since a nice-looking physique will come as a

by-product of hard work. With this being said, it's

upsetting to see how many athletes still refer to the

popular body-building magazines for their strength

training advice. Strength training for athletic

performance needs to be purpose-driven, and that purpose

depends upon the needs of the sport, not the desire for

a particular body part to look a certain way.

For

the majority of sports, I have determined that there are

four truths when considering strength training and

sports performance:

1) In all sports that

involve athleticism (speed, strength, power, agility,

mobility) athletes who can produce and reduce high force

at high speed are at an advantage.

2) Speed of

movement, strength, and explosive power are related;

athletes with higher power to body weight ratios execute

faster, and dominate athletics.

3) Just building

big muscles, lifting heavy weights, or doing Olympic

lifts is not good enough; you need to implement several

methods of training to optimally develop sports

performance.

4) By doing the proper lifts, jumps,

and sprints, you will increase the horsepower of your

vehicle--which is your body.

From the perspective

of these truths we can see that athletes cannot just

depend on heavy strength training alone. They need to be

involved in a program that implements a complete regimen

of muscle actions (concentric, eccentric, isometric),

training speeds, and intensities. And that's where

conjugate training comes in.

What is conjugate

training? Conjugate means to join together. To train

using multiple methods within one workout, or over the

course of one block of workouts (microcycle). Strength,

power, hypertrophy, speed, and agility can be

progressively developed simultaneously in a conjugate

multi-method program.

The most fundamental

components of a strength training program are the amount

of weight lifted (overload) and the speed of the

repetition (tempo). Vladimir Zatsiorsky, Ph.D.--a

world-renowned strength scientist, author, and professor

at Penn State University--determined that there are

three distinct methods for developing force within

skeletal muscle fibers. These three methods are

responsible for overloading the fast twitch muscle

fibers (type IIa and IIb) innervated by the fast motor

units (fast oxidative glycolitic, and fast fatigable). I

call this "Targeted Overload," and the methods

are:

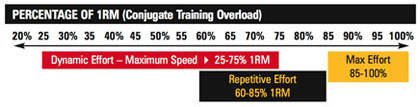

Maximum Effort:

Maximal Strength

(strong reps)

Heavy training, using 85-100 percent of a one rep

max (1RM)

Dynamic Effort:

Explosive

Strength (speed reps)

Explosive training, using sub-max weights at max

speed

Plyometrics--stretch shortening cycle (SSC)

activities

Speed and agility training

Repetitive

Effort:

Hypertrophy Strength (burn reps)

Training to a point of muscular fatigue using

sub-max weights

Lactate tolerance training

Work capacity training

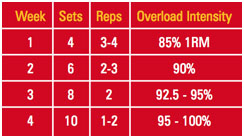

Max-effort training is

used to develop the high threshold fast-twitch muscle

fibers. But be careful, attempting to lift weights that

are too heavy is counterproductive. Athletes should

never attempt to lift weights that are so heavy that

someone else has to lift it off of them, or that cause

them to use poor technique to force the weight up. Below

is a sample max effort cycle:

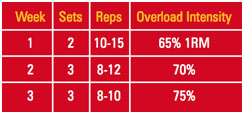

The next

method of overload--"dynamic effort" training--is used

to activate your fast twitch muscle fibers in an

explosive manner. When using this method of overload the

rate of force development (bar speed) is key. The weight

should not be heavy in comparison to the max effort day.

Rate of force development, your body's ability to

recruit motor units and fire muscles, is what you're

training. Below is a sample dynamic effort cycle:

The last

method of overload, "repetitive effort," is used to push

the muscles to produce force in a fatigued state. The

athlete's muscles should experience a burning on the

last few reps of the set. It's important not to take the

sets to complete failure, but rather to a point of

fatigue, one to two reps short of total failure. When

you get to the point of failure, exercise technique

generally becomes sloppy. Below is a sample repetitive

effort cycle:

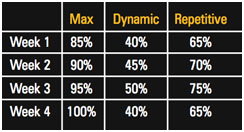

Cycling/Periodization

You

can't train the same exercises with weights above 90

percent for much longer than three weeks before your

nervous system begins to weaken. When this happens

strength gains will begin to diminish and accumulative

fatigue will cause the athlete to plateau. For this

reason training must be cycled with fluctuations in

exercise selection, intensity, and volume

(periodization). The best way around this three-week

barrier is to switch the exercises used for the max

effort method every one to three weeks. This keeps the

body fresh so the method can be cycled year round. Below

are the guidelines for cycling:

Keep all workouts between four to six total

exercises.

Do only one max effort workout per week for the

upper body and one for the lower body primary strength

exercises (i.e., squat, deadlift, bench press, pull-ups,

rows).

Do one dynamic effort workout per week for the upper

body and one for the lower body primary strength

exercises (i.e., squat, power clean, bench press,

pull-ups, rows).

Use the repetitive effort method for your

supplemental and auxiliary exercises every workout

(i.e., sled pulls, shoulder and rotator cuff work,

triceps, bicep, forearms and abs).

Take an active rest week after every three max

effort cycles (12 weeks) to allow for complete

restoration (i.e., cross train and play another sport,

get out of the weight room but don't just sit

around).

Stop repetitive effort sets one to two reps short of

complete muscle failure. This assures the athlete will

always use good lifting technique and not overtax the

muscles.

Here's the intensity progression for the

three methods together for a four-week period.

To build their

best body, athletes need to do multi-joint strength

training exercises with the collective goal of

developing muscle mass, strength, and power.

Multi-Joint Exercises

The first thing

you must help athletes grasp and believe is this; the

body is one functional unit. If you isolate and train

one muscle group and neglect others you develop

imbalances, which can eventually lead to injury. For

optimal sport performance the body must be trained as an

athletic machine, one that functions as the collective

sum of its parts.

There's a saying in athletic

strength and conditioning that it's better to train

movements and not just muscles. The nature of most

sports is to make ground based, multi-joint movements

and not isolated single-joint movements. With this in

mind strength training should be specific and follow

suit.

In the weight room isolating your

quadriceps (leg extensions), hamstrings (leg curls),

glutes (hip extensions), and calves (heel raises) is

isolated muscle building, whereas using ground based,

multi-joint exercises such as squats, dead lifts, and

hang cleans are movement building. Movement building

activates the neuromuscular system in similar firing

patterns as it's called upon in sport, and therefore has

a greater transfer to athletic performance. Below is a

list of the most useful multi-joint exercises:

Upper body:

Bench presses (flat, incline, decline)

Pull-ups

Chin-ups

Pulldowns

Rows (bent over, seated, and upright)

Shoulder presses (military and behind the neck)

Lower/Total body:

Squats (deep, parallel, half squats, front squats,

lunges, split squats)

Dead lifts (conventional, sumo, Romanian, good

morning)

Olympic lifts (cleans, jerks, snatches)

In order

to take their performance to the next level, athletes

must start by taking their strength training to the next

level. Cycle the three methods of overload with

multi-joint exercises, and consume the right foods at

the right times, followed by adequate rest, and they'll

be well on their way to a stronger, more-athletic body.

Train them hard, and most importantly train them smart.

About the author:

Greg Werner

is director of strength and conditioning at James

Madison University, and owner of AthElite Strength &

Conditioning Academy.

|

References:

Vladimir M. Zatsiorsky, 1995, Science and Practice

of Strength Training, Human Kinetics.

Mel Siff and Yuri V Verkhoshansky, 1999, Super

Training: Strength Training for Sporting Excellence. 4th

edition, Supertraining International.

John Ivy and Robert Portman, 2004, Nutrient Timing

System, Basic Health.

| |

Official

Site of the James Madison University Strength & Conditioning Program

Official

Site of the James Madison University Strength & Conditioning Program