Two Casualties of Apartheid

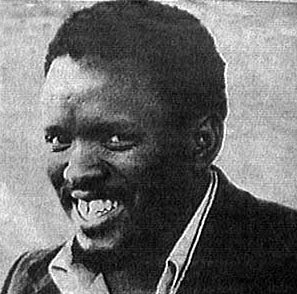

Influenced by militant civil rights groups in the

United States, Steve Bantu Biko founded South Africa's black consciousness

movement in 1968. Throughout the 1970s, Biko encouraged black South

Africans to form anti-apartheid organizations independently from white

groups. He promoted "Black power" which stressed racial pride, self-reliance

and active resistance to white rule. Biko served as the first president

of South Africa's Student Organisation (SASO) and participated in the Soweto

Uprising of 1976. His involvement in anti-apartheid protest led to

several arrests and visits to prison; in [] Biko was banned from.....

On

August 18, 1977, police again arrested Biko and his friend Peter Jones

under the Terrorism Act, a law that sanctioned unlimited detention for

the purpose of interrogation. After having spent the night in a local

prison, Biko was detained in a cell in Port Elizabeth where he was stripped

naked so that, according to police, he would not use his clothes to hang

himself. On September 6, the naked Biko was transported to police

headquarters where Major Harold Snyman and four other security officers

- Daniel siebert, Jacobus Beneke, Rubin Marx, and Gideon Nieuwoudt.

- began Biko's interrogation at 9:00 am.. At some point during the

next thirty minutes, a "scuffle" erupted between Biko and the officers

after Biko refused to answer their questions and instead seated himself

in a chair. During the incident, Biko suffered a severe trauma to

the head and quickly became disoriented. Officers left Biko shackled

to a metal grille in the hallway. Although the injured Biko was blurring

his speech and had lost control of his bodily functions, the officers did

not call for medical help until the next day. On September 8th, two

district doctors ordered that Biko be taken to a hospital. At the

hospital, additional examination revealed massive brain damage but Biko

was returned to prison despite his deteriorating physical condition (a

decision accepted by the doctors, Benjamin Tucker and Ivor Lang).

On September 11, Biko collapsed in his cell. In the evening, officers

placed Biko, clothed only in underpants, into the back of a Land Rover

and covered him with blankets. Biko was driven 750 miles to Pretoria

where he died the next day..

On

August 18, 1977, police again arrested Biko and his friend Peter Jones

under the Terrorism Act, a law that sanctioned unlimited detention for

the purpose of interrogation. After having spent the night in a local

prison, Biko was detained in a cell in Port Elizabeth where he was stripped

naked so that, according to police, he would not use his clothes to hang

himself. On September 6, the naked Biko was transported to police

headquarters where Major Harold Snyman and four other security officers

- Daniel siebert, Jacobus Beneke, Rubin Marx, and Gideon Nieuwoudt.

- began Biko's interrogation at 9:00 am.. At some point during the

next thirty minutes, a "scuffle" erupted between Biko and the officers

after Biko refused to answer their questions and instead seated himself

in a chair. During the incident, Biko suffered a severe trauma to

the head and quickly became disoriented. Officers left Biko shackled

to a metal grille in the hallway. Although the injured Biko was blurring

his speech and had lost control of his bodily functions, the officers did

not call for medical help until the next day. On September 8th, two

district doctors ordered that Biko be taken to a hospital. At the

hospital, additional examination revealed massive brain damage but Biko

was returned to prison despite his deteriorating physical condition (a

decision accepted by the doctors, Benjamin Tucker and Ivor Lang).

On September 11, Biko collapsed in his cell. In the evening, officers

placed Biko, clothed only in underpants, into the back of a Land Rover

and covered him with blankets. Biko was driven 750 miles to Pretoria

where he died the next day..

At Biko's inquest in 1978, Snyman maintained that

Biko had fallen and hit his head against a wall during the "scuffle."

According to the officers who testified, a "wild-eyed" Biko had attacked

them and they were only trying to restrain the prisoner, not to kill him.

Donald Woods, a journalist and friend of Biko, called the inquest "shockingly

farcical" because key evidence that would have incriminated the police

had been suppressed.

In

the summer of 1993, Amy Biehl, a 26 year-old American, was in South Africa

on a Fulbright scholarship. She had recently graduated from Stanford

University with a degree in political science and had come to South Africa

to assist in a voter registration program for the upcoming April 1994 election

- the nation's first non-racial election since the fall of apartheid.

In

the summer of 1993, Amy Biehl, a 26 year-old American, was in South Africa

on a Fulbright scholarship. She had recently graduated from Stanford

University with a degree in political science and had come to South Africa

to assist in a voter registration program for the upcoming April 1994 election

- the nation's first non-racial election since the fall of apartheid.

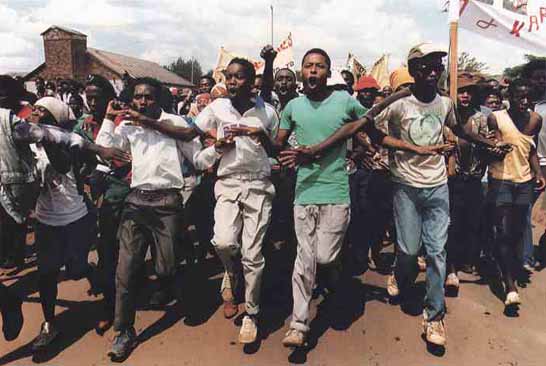

On August 25, 1993, three days before her scheduled

return to the U.S., Biehl was driving three black co-workers home to a

township outside of Cape Town when a group of young blacks began hurling

rocks at the car. The rocks struck Biehl in the face and she stopped

the car. The attackers then surrounded the vehicle, chanting a PAC

slogan, "one settler [white person], one bullet." They dragged Biehl

from the car who, as she attempted to flee, was hit by a brick, beaten,

and stabbed. Her co-workers had yelled to the men that Biehl was

a "comrade" but to no use. After police arrived, the youth disbanded

and Biehl was driven to the nearest police station where she died from

her injuries. That same day, police also responded to a series of

incidents in the area in which black youths threw stones at white delivery

truck drivers as part of a student strike on behalf of black teachers.

Their goal had been to disrupt local white businesses in order to draw

attention to their cause.

After her death, her father Peter Biehl stated,

"We didn't consider Amy to have been a victim. She was doing what

she wanted in life, and she was well aware of the risks and rewards."

On

August 18, 1977, police again arrested Biko and his friend Peter Jones

under the Terrorism Act, a law that sanctioned unlimited detention for

the purpose of interrogation. After having spent the night in a local

prison, Biko was detained in a cell in Port Elizabeth where he was stripped

naked so that, according to police, he would not use his clothes to hang

himself. On September 6, the naked Biko was transported to police

headquarters where Major Harold Snyman and four other security officers

- Daniel siebert, Jacobus Beneke, Rubin Marx, and Gideon Nieuwoudt.

- began Biko's interrogation at 9:00 am.. At some point during the

next thirty minutes, a "scuffle" erupted between Biko and the officers

after Biko refused to answer their questions and instead seated himself

in a chair. During the incident, Biko suffered a severe trauma to

the head and quickly became disoriented. Officers left Biko shackled

to a metal grille in the hallway. Although the injured Biko was blurring

his speech and had lost control of his bodily functions, the officers did

not call for medical help until the next day. On September 8th, two

district doctors ordered that Biko be taken to a hospital. At the

hospital, additional examination revealed massive brain damage but Biko

was returned to prison despite his deteriorating physical condition (a

decision accepted by the doctors, Benjamin Tucker and Ivor Lang).

On September 11, Biko collapsed in his cell. In the evening, officers

placed Biko, clothed only in underpants, into the back of a Land Rover

and covered him with blankets. Biko was driven 750 miles to Pretoria

where he died the next day..

On

August 18, 1977, police again arrested Biko and his friend Peter Jones

under the Terrorism Act, a law that sanctioned unlimited detention for

the purpose of interrogation. After having spent the night in a local

prison, Biko was detained in a cell in Port Elizabeth where he was stripped

naked so that, according to police, he would not use his clothes to hang

himself. On September 6, the naked Biko was transported to police

headquarters where Major Harold Snyman and four other security officers

- Daniel siebert, Jacobus Beneke, Rubin Marx, and Gideon Nieuwoudt.

- began Biko's interrogation at 9:00 am.. At some point during the

next thirty minutes, a "scuffle" erupted between Biko and the officers

after Biko refused to answer their questions and instead seated himself

in a chair. During the incident, Biko suffered a severe trauma to

the head and quickly became disoriented. Officers left Biko shackled

to a metal grille in the hallway. Although the injured Biko was blurring

his speech and had lost control of his bodily functions, the officers did

not call for medical help until the next day. On September 8th, two

district doctors ordered that Biko be taken to a hospital. At the

hospital, additional examination revealed massive brain damage but Biko

was returned to prison despite his deteriorating physical condition (a

decision accepted by the doctors, Benjamin Tucker and Ivor Lang).

On September 11, Biko collapsed in his cell. In the evening, officers

placed Biko, clothed only in underpants, into the back of a Land Rover

and covered him with blankets. Biko was driven 750 miles to Pretoria

where he died the next day..

In

the summer of 1993, Amy Biehl, a 26 year-old American, was in South Africa

on a Fulbright scholarship. She had recently graduated from Stanford

University with a degree in political science and had come to South Africa

to assist in a voter registration program for the upcoming April 1994 election

- the nation's first non-racial election since the fall of apartheid.

In

the summer of 1993, Amy Biehl, a 26 year-old American, was in South Africa

on a Fulbright scholarship. She had recently graduated from Stanford

University with a degree in political science and had come to South Africa

to assist in a voter registration program for the upcoming April 1994 election

- the nation's first non-racial election since the fall of apartheid.