Section 1.1 Learning Mathematics

¶I assume that you want to be successful in learning mathematics. It might be true, however, that your past experiences make you doubt this as a possibility. Before we start talking about actual mathematics, let's have a discussion about what it means to learn mathematics and how to approach this more successfully.

Subsection 1.1.1 How People Learn

This section is based on my reading, understanding and interpretation of a report issued by the National Research Council in 2000 called How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience and School and a follow-up report in 2005 focused more directly on mathematics, How Students Learn: Mathematics in the Classroom. Although there is a lot to digest, I would encourage you to read some of this if you want more background. I hope to convey some key points that I hope will be especially helpful in focusing our efforts in learning.

Let us start with some questions. What does it mean to learn? Can we become more effective at learning?

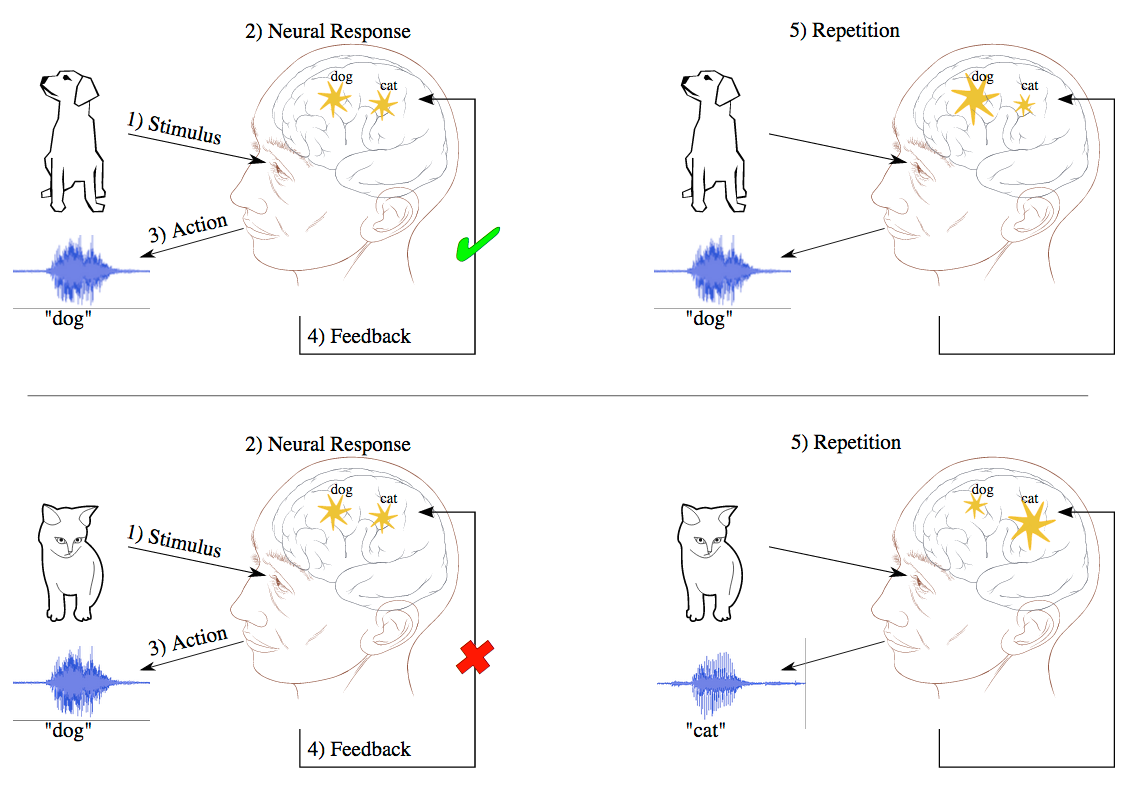

Studies of brain activity reveal that learning physically changes the structure of the brain. The brain consist of neurons (brain cells) that form networks. Any particular neuron has dendrites which receive signals from other neurons. When the total signal received by a neuron reaches a critical threshold, the neuron will produce its own signal which it transmits along its axon to synaptic connections with the dendrites of other neurons. External stimuli trigger patterns of neuron firing responses which are ultimately translated into memories and actions. Learning consists of transforming these networks so that the firing patterns change. Feedback (both positive and negative) is necessary to weaken connections that are not desired and to create and strengthen connections that are desired.

Early attempts to measure learning (which pre-date the understanding of the brain), especially when studying animal models like rats in maze, considered learning as behavior that is reinforced by a stimulus. An example is given of a cat trapped in box with an exit that opens when a particular string is pulled. By (frantic) trial and error, the cat eventually opens the box. When put back in the box, the cat will not immediately repeat the necessary action to escape; it takes a number of repetitions for the action to be reinforced by the reward before the cat learns to attempt the particular action immediately in order to escape. Using modern understanding of the brain's neural networks, the negative feedback (from being trapped) and the positive feedback (from being released and rewarded) established new neural connections that triggered pulling the release when the cat found itself in the trapped environment.

Memorization of facts using flashcards or online drills can be interpreted in the context of this model of learning. A presented statement (the clue or question) provides a stimulus. Recalling the desired response (the answer) is the behavior desired from that response. Success or failure and the resulting emotional responses during training provide the feedback for the new network connections to be formed. Unfortunately, memorization of facts is not an effective learning approach when dealing with more abstract problem solving scenarios.

Views of learning have expanded to consider learning with understanding wherein learning is not just a reinforced behavior but a cognitive effort (thought) built on a framework (understanding). Learning therefore is not just a filing system of individual memories; it is structured according to some organizational process that itself involves neural feedback. One of the key distinctions that has been identified between novices and experts in a problem-solving area is that an expert has a rich body of knowledge that is organized around core concepts as opposed to a list of facts or strategies.

Thus, we see that learning requires more than just the memorization of facts, processes and strategies; it requires developing a mental framework by which information is organized. These steps require that we undertake processes by which neural network connections in our brain are rewired, breaking connections that correspond to misconceptions and poor organization and developing new connections that correspond to more effective knowledge and organization. This requires a significant level of interaction with the material that we wish to learn in order to effect such a change.

Subsection 1.1.2 Best Practices for Learning

How People Learn identified three basic principles to guide effective learning.

Because students approach learning with preconceptions, these understandings must be engaged or else learning will be superficial or thwarted.

Developing competence requires (a) a deep foundation of factual knowledge, (b) a conceptual framework by which these facts and ideas are understood, and (c) an organized memory system that facilitates retrieval and application of that knowledge.

Students should take control of their own learning by defining learning goals and monitoring their progress in achieving them.

We should attempt to frame our learning experiences so that these three principles are implemented.

One key aspect of this framing has to do with our mindset. Mindset refers to our own ideas about how we learn. We have a fixed mindset when we believe that our intelligence is predetermined and our ability to learn is limited. We have a growth mindset when we believe that our intelligence can grow and we can learn anything with enough effort.

Jo Boaler, a mathematics education expert on mindset, has a fascinating project on mathematical mindset and mathematical learning, youcubed.org, in which she emphasizes the following three key points about our attitude and approaches to learning.

- Anyone can learn to high levels.

- Mistakes and struggle are good for brain growth.

- Visualization of mathematics helps develop our brain connections.

I highly recommend watching some of the videos that she has developed.

Subsubsection 1.1.2.1 Engaging Preconceptions

Preconceptions represent the sum of all knowledge accumulated as well as the manner in which that knowledge is organized and interpreted. Valid preconceptions provide the necessary foundation on which additional knowledge accumulates. Unfortunately, it is often the case that preconceptions might also be an obstacle for learning. This may be due to something learned incorrectly. But it can just as often be something learned correctly but organized in a way that obscures generalizations necessary to advance in learning.

Engaging our preconceptions involves recognizing exactly what our preconceptions may be. For valid preconceptions, we integrate new knowledge into our system of understanding and it is held more tightly than if we did not connect it to our existing knowledge. For invalid or obstructive preconceptions, we face an uncomfortable cognitive dissonance that may require dismantling and reconstructing our framework of understanding so that future learning can proceed.

Subsubsection 1.1.2.2 Developing and Organizing a Deep Foundation of Knowledge

The second principle focuses on the knowledge itself and how we organize our thinking about that knowledge. We start with the need for a deep foundation of facts. However, we should notice that the factual knowledge alone is really just one component of this learning principle. At first glance, I thought the second and third components—a conceptual framework and an organized memory system—were the same thing. Then I saw that although they could be related, they emphasize two different aspects.

The conceptual framework is about how the facts and ideas are understood. This is how we make sense of the facts, how we relate them with one another, and how we interpret them. Effective learning requires developing this framework as we add knowledge to our memory.

The organized memory system refers to our methods and strategies for recall. Consider how we can organize files on a computer drive. We could adopt a flat filing system where every file is in a single location, distinguished only by name; or we could adopt a hierarchical filing system with folders or directories organized in a way that related files are grouped together. More modern storage strategies include tagging files (e.g., hashtags), which may be easier to relate to memory. Imagine that our memories work in a similar way, that we can establish tags that go along with the knowledge. By thinking about the relevant tags as a stimulus for our mind, we can trigger our memory to recall that desired knowledge.

Subsubsection 1.1.2.3 Metacognition and Taking Control of Your Learning

The third principle states that students should take control of their own learning. Each student should establish clear learning goals and monitor their progress. This requires thinking about their thinking, reflecting on their own understanding and effectiveness in organizing their knowledge. This process is called metacognition. Metacognition allows us assess our own progress and identify our strengths and weaknesses. It allows us to recognize when we need additional help. It is essential to make these assessments while our knowledge and skill set are still forming. When we recognize our weaknesses, we can adapt our learning methods and accelerate our progress. We shouldn't wait for a class exam to decide we don't understand.

Subsection 1.1.3 What's Class Got to Do With It?

As the understanding of how we learn has grown, experts recommend that our educational settings and environments be designed to facilitate effective learning. Four design characteristics summarize what we want to create effective learning. The environment should be (1) learner-centered, (2) knowledge-centered, (3) assessment-centered, and (4) community-centered.

In a learner-centered classroom, the educational experiences give attention to students' ideas, knowledge, skills, and attitudes. There is an awareness that existing ideas can lead to misconceptions as well as a path to new understanding. Student experiences as well as the ways students reflect and understand these experiences will be different for different individuals. Consequently, students must be individually engaged in the educational experience. This is strongly related to the idea that brain growth occurs during the struggle of learning new things.

In a knowledge-centered classroom, the educational experiences provide clear guidance on what is intended for learning, and those experiences are designed to develop understanding of that knowledge. Effective knowledge involves both the content matter and an understanding of the context, relationship, and application of that matter. Knowledge-centered learning helps students create an effective mental organization by identifying core connected ideas.

Assessment-centered education emphasizes that both the learner and the educator need to assess the progress of learning and understanding. Assessment helps make learning and understanding visible to both the student and the teacher during the learning process and not just through formal evaluation. Instruction that helps students become aware of their own progress through informal assessments provides them with opportunities to revise and improve their thinking. In-class activities where students engage in material and evaluate their own progress are examples of such informal assessment opportunities. In response to these assessment opportunities, students can develop their metacognitive abilities and learn to evaluate the effectiveness of their strategies in learning.

A community-centered classroom establishes norms of behavior and connections to the world that support core learning values. In our classes, we encourage the processes of development, questioning, and progress. Because our minds grow more when we make mistakes, we welcome mistakes. They do not measure inadequacy but are evidence of a healthy struggle to learn. We also encourage taking emotional risks that are part of asking questions or suggesting alternative approaches. At the same time, the classroom never has room for comments or behaviors that degrade, belittle, or hurt others. In summary, a community-centered classroom seeks to establish an environment that encourages a growth mindset.